The dreidel is perhaps the most famous custom associated with Hanukkah.

However, the dreidel game originally had nothing to do with Hanukkah; it has been played by various people in various languages for many centuries. It seems that spinning tops like dreidels were popular throughout the ancient Middle East.

Many believe that in 175 BCE, when the wicked Greek King Antiochus had forbidden all Jewish religious worship, the Jews created the dreidel for them to learn Hebrew and study the Torah in secret.

The dreidel was a spinning top and a popular gambling device at that time. Jews studied the Torah orally with the use of dreidels, pretending to play them, so if Greeks raided these Torah scholars, they would find “gamblers” instead. This way, the Greeks would leave the Jews alone.

When Hebrew was revived as a spoken language, the dreidel was called, among other names, a ‘sivivon’, from the Hebrew word ‘sov’, meaning ‘spin’.

Some believe that this story is just a legend. The exact origins of the dreidel game remain unclear, although evidence suggests that gamblers from Babylon used blocks decorated with images of Ishtar and Ninurta (Roman counterparts of Venus and Saturn) that symbolized winning and losing.

According to an anthology about Jewish holidays called ‘Sefer Hamoadim’, the dreidel was created in ancient Rome or Greece, and brought to England by Roman settlers or soldiers. This explains why some English tops bear Latin/Roman letters.

Most scholars agree that the dreidel may have originated from the English spinning top called a ‘teetotum’ dating to ancient Greek and Roman times. Dreidels were made from all sorts of materials, in ancient times clay, but today silver and wood seem to be especially traditional.

These are the letters A, D, N, and T. A stands for ‘aufer’, which translates as ‘take from the pot’; D stands for ‘depone’, which means ‘put into the pot’; N for ‘nihil’, meaning ‘nothing’; and T for ‘totum’, or ‘take all.’

Yiddish-speaking Jews gave the name ‘dreidel’ to the spinning top and the game. The term came from the German word ‘drehen’ which means ‘to spin.’ They also replaced the letters with their Hebrew counterparts.

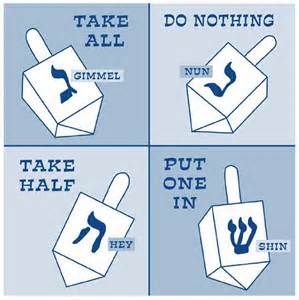

The new letters on the dreidel mean the same, but G became gimel or ‘all,’ H became ‘hey’ or ‘half,’ N became ‘nun’ or ‘nothing,’ and S became ‘shin’, meaning ‘put in.’ These Hebrew letters inscribed on the dreidel’s sides make up the acronym for the Hebrew saying ‘Nes Gadol Hayah Sham,’ which can be translated as ‘A great miracle occurred there.’

This is in reference to the miracle which is what Hanukkah is all about, – the recovery of Jerusalem and the subsequent rededication of the Second Temple.

In England and Ireland there is a game called ‘totum’ or ‘teetotum’ that is especially popular at Christmastime. In English, this game is first mentioned as ‘totum’ ca. 1500-1520. The name comes from the Latin ‘totum’, which means ‘all.”’ By 1720, the game was called ‘T- totum’ or ‘teetotum’, and by 1801 the four letters already represented four words in English: T = Take all; H = Half; P = Put down; and N = Nothing.

In Hebrew, each letter has a numerical value. The numerical value of the dreidel’s nun, gimmel, hey and shin is 358. This is also the numerical value of some key words in Hebrew. It’s the same as ‘Nachash’ – the snake that tempted Adam and Eve to eat the fruit from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge in the book of Genesis. It’s also the numerical value of the Hebrew word ‘Moshiach’, or Messiah, who will ultimately redeem the Jewish people.